By Dr. Keertana Anne and Dr. Elena Perez

Next Lesson - Dementia

Abstract

- Meningitis is an acute inflammation of the meninges.

- There are many different causes of meningitis, both infectious and non-infectious.

- Most patients present with a headache and neck stiffness.

- Bacterial meningitis is the most dangerous type and must be investigated and treated rapidly.

- Treatment is by managing symptoms, giving corticosteroids, and giving empirical antibiotic therapy (if needed).

- Encephalitis is a condition of inflammation of the brain parenchyma.

- Prion diseases refer to brain damage caused by abnormal prion proteins that aggregate at the synapse and cause a spongiform appearance of the brain as neurones are destroyed.

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease can occur sporadically, be inherited due to familial mutations, or be acquired through ingestion, leading to variant CJD, which is associated with dietary exposure to bovine spongiform encephalopathy and typically follows a different, often longer, clinical course.

Core

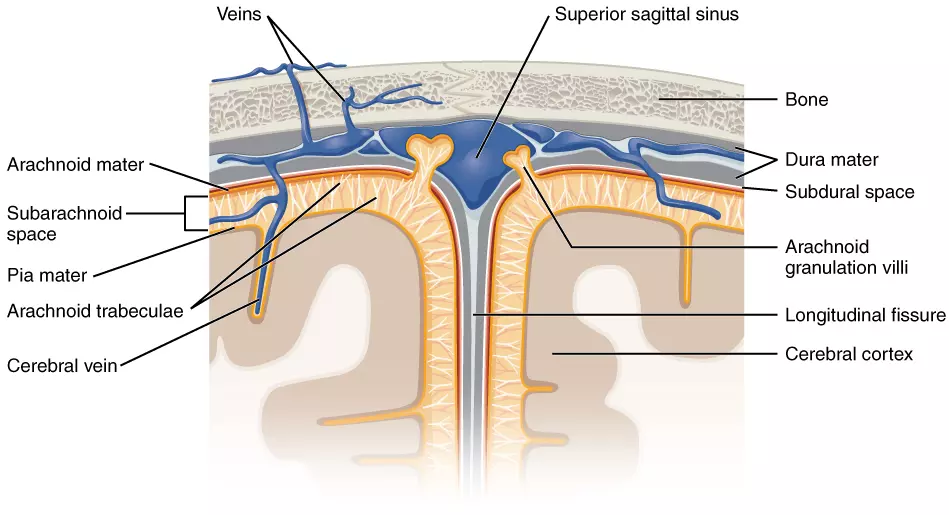

Meningitis is a condition caused by acute inflammation of the leptomeninges, which includes the pia and arachnoid mater that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Diagram - The meningeal layers surrounding the brain. The pia and arachnoid mater are inflamed in patients with meningitis

Creative commons source by OpenStax [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

The causes of meningitis can be split into infectious or non-infectious.

Infectious causes can include localised bacterial, viral or fungal infections or systemic infections such as tuberculosis, syphilis or Lyme disease.

Non-infectious causes can be as a result of cancer, drugs (NSAIDs and certain antibiotics), or secondary to systemic disorders such as sarcoidosis.

Viral infections account for the majority of meningitis cases worldwide; however, bacterial meningitis is associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality and therefore requires urgent recognition and treatment. The causative organism of bacterial meningitis depends on a multitude of factors, primarily the age of the patient.

- In neonates - Escherichia coli, Group B streptococcus and Listeria monocytogenes. Neonatal meningitis in particular has an incredibly high morbidity and mortality rate

- In children aged 3 months and older - Neisseria meningitidis (also known as meningococcal meningitis) and, less commonly in vaccinated populations, Haemophilus influenzae type B

- In adults - Streptococcus pneumoniae and Listeria monocytogenes

Bacterial meningitis is spread primarily by respiratory droplets and aerosol transmission. Prolonged contact is required with a carrier to develop the infection which is why close contacts of the patients (especially those living in the same household) are given prophylactic treatment. See the section on management of contacts below.

In bacterial meningitis, the infection can spread to the meninges via two separate routes: via the bloodstream (bacteraemia), and when there is any direct contact between the meninges and the nasal cavity or skin.

Bacteraemic spread takes place following a local nasopharyngeal colonisation that can invade the meninges, specifically in areas that have a thin or damaged blood-brain barrier (such as the choroid plexus). These cause a localised inflammation, due to the action of the central nervous system’s immune defences (astrocytes and microglia) and the resulting inflammation increases the permeability of the blood-brain barrier.

Direct contact with the meninges can arise from traumatic events, iatrogenic infection spread (such as following the insertion of indwelling devices) or congenital defects.

Patients with meningitis commonly present with a severe headache and neck stiffness, although not all features are present in every patient. Some may also develop an altered mental state, developing neurological symptoms such as confusion, irritability and drowsiness. Other symptoms may include fever, photophobia, nausea and vomiting and a non-blanching rash.

It is rare for children to present with specific symptoms like headache or neck stiffness, and parents may just complain that their child is feverish, irritable, vomiting or refusing feeds. Clinicians must have a high suspicion of bacterial meningitis when examining a young child with a suspected acute infection.

The patient’s whole body should always be appropriately exposed and examined when suspecting meningitis, to investigate and assess for the non-blanching rash. This can appear as petechiae or purpura, which are erythematous lesions that are either smaller (petechiae) or larger (purpura) than 2mm in diameter. They are formed due to the leakage of blood from inflamed vessels and therefore permeable capillary vessels.

The ‘glass test’ or the ‘tumbler test’ can be used to assess whether the rash blanches under pressure. The presence of this rash can indicate meningococcal septicaemia, and the patient should be managed rapidly.

Image - A purpuric rash. These are lesions larger than 2 mm, and can be seen in patients with meningococcal septicaemia. The rash is non-blanching

Creative commons source by Hektor [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Two specific physical signs that can be elicited for meningitis include Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. Positive tests are seen due to the meningeal irritation caused by the movement of the spinal cord within the meninges.

- Kernig’s Sign - The patient is unable to straighten their leg when the hip is flexed to 90o.

- Brudzinski’s Sign - When the patient’s neck is flexed, their knees and hips will also flex.

Bacterial Meningitis vs Meningococcal Septicaemia

It is important to differentiate between bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia.

Bacterial meningitis is an acute infection of the meninges caused by bacteria, which can include Neisseria meningitidis as well as other organisms listed above. While the primary site of infection is the meninges, patients may also show systemic features of infection.

Meningococcal septicaemia is a disseminated infection causing organ dysfunction (sepsis) caused by Neisseria meningitidis. This infection commonly originates in the meninges but could technically come from any source of a Neisseria meningitidis infection. Due to the systemic nature of meningococcal septicaemia, it is this condition that causes the non-blanching rash.

Before beginning any specific investigations for meningitis, the patient should be screened for any signs of meningococcal septicaemia. This should be managed using the Sepsis 6 Bundle before any further investigations are carried out.

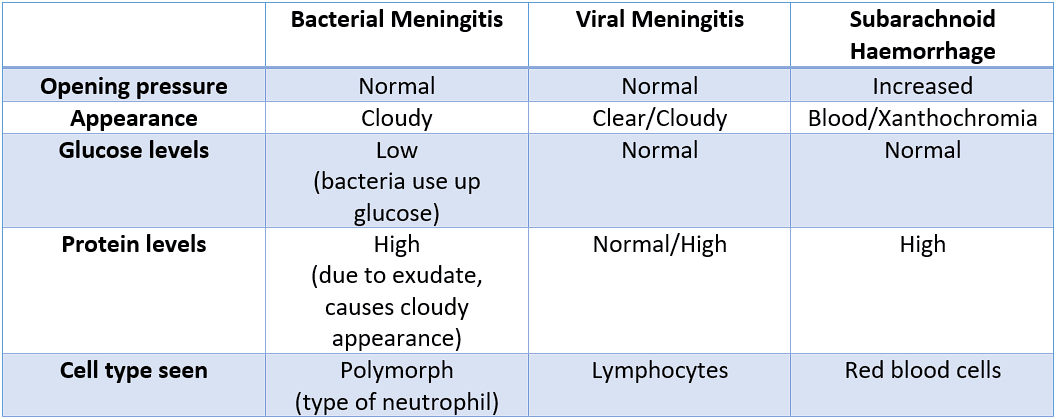

All patients with suspected meningitis (especially bacterial) should have a lumbar puncture, unless they are thought to have a raised intracranial pressure. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collected from the procedure should be sent to the lab for assessment, looking in particular at any causative organisms present (gram staining, culture and sensitivity) and the biochemistry of the fluid (protein, glucose and lactate levels). The lumbar puncture also allows clinicians to rule out a diagnosis of a subarachnoid haemorrhage, which can present similarly (see our article on Subarachnoid Haemorrhage).

The table below shows the results that may come back from the lumbar puncture.

Table - Lumbar puncture results for differentials of a patient presenting with meningitis symptoms

SimpleMed original by Dr. Keertana Anne

Normally, a lumbar puncture has a clear appearance, normal glucose and low protein levels, and no abnormal cell types are seen.

Other investigations that should be performed include basic observations and blood tests, a neurological assessment (see our article on the Reticular Formation for more information about neurological assessments), blood cultures (should be taken before antibiotics are given) and a nasopharyngeal swab.

Managing the Patient

In all patients with meningitis, general management measures should take place. These include providing adequate pain relief, antipyretics, fluid and nutritional support if required, placing them in a dark room to relieve any photophobia and positioning their head up.

Patients with bacterial meningitis need to be monitored more closely and treated aggressively due to the high mortality rate of the disease. All patients with suspected bacterial meningitis must be given empiric antibiotic therapy, preferably after the blood cultures and lumbar puncture have been performed. However, if there is expected to be a delay in the availability of these tests, antibiotic therapy must be started immediately. The choice of antibiotic depends on the age of the patient and can vary based on local guidelines.

Corticosteroids, in the form of dexamethasone, should be considered in selected patients with suspected or confirmed bacterial meningitis, particularly where pneumococcal infection is suspected. When indicated, this should be given before or with the first dose of antibiotics to reduce inflammatory complications.

Managing Contacts

The close contacts of a patient with confirmed meningitis should be offered prophylactic antibiotic treatment as soon as possible. This includes members of their household and anyone who has been exposed to respiratory secretions from the infected patient, such as those who share an office at work or a desk at school. The risk of developing the disease is highest in the first 7 days following contact but remains present for up to 4 weeks after.

Vaccinations

There are three vaccination programmes available that target different groups of meningococcal disease.

- The Meningococcal group B (MenB) vaccination is given to babies at 2, 4 and 12 months. MenB is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in the UK in children.

- The Haemophilus influenzae type b and meningococcal group C (Hib/MenC) booster is given at 12-13 months, primarily to boost protection against Hib, with MenC disease now largely controlled through wider vaccination programmes.

- Due to the increase in the number of cases presenting with meningococcal group W disease, the MenACWY vaccine is being regularly offered to children in school, around the age of 14. Children who did not receive the vaccine at a younger age are also offered it between the ages of 17-18, or just before they go to university.

See our article on Childhood Immunisations for more information.

Most patients make a full recovery from meningitis; however, a handful can end up with some serious complications. The complications are dependent on the extent of the damage done, how quickly treatment was given and which surrounding structures were affected.

Complications can include hearing or vision loss (either partial or total), behavioural problems and issues with memory, concentration, coordination and movement. Disseminated infection, such as that seen in meningococcal meningitis can also affect other organs such as bones, joints and the kidneys.

Encephalitis is a condition of inflammation of the brain parenchyma itself, usually caused by viral infections.

Examples of viral infections that cause encephalitis in the UK include:

- Herpes Simplex

- Varicella Zoster

- Mumps virus

- Measles virus

- Influenza

Worldwide, viral infections such as West Nile virus can be transmitted via vectors like mosquitos.

Symptoms of encephalitis initially present similarly to meningitis: fever, headache, nausea, neck stiffness and photophobia are all common. As the infection progresses, features may emerge that differentiate from meningitis, most commonly seizures. However, in a child, seizures may be a result of the fever, making differentiation trickier.

Encephalitis is diagnosed through lumbar puncture. A CT scan may be performed beforehand if there are clinical features suggesting raised intracranial pressure.

Management of encephalitis is initially identical to meningitis with antivirals (acyclovir) and antibiotics (commonly ceftriaxone).

Prion proteins are physiological compounds found in the synapses in the brain although little is yet understood of their function. However, these prion proteins (PrP) can transform via sporadic mutations and acquire an abnormal form, then known as PrPsc. This can also be the result of the inheritance of a mutated gene or following ingestion of PrPsc from contaminated foods.

Prions are responsible for spongiform encephalopathies. They are named for the sponge-like appearance of the brain seen at autopsy, which results from neurone death caused by aggregation. Common forms of the disease are seen across the food chain and a few common presentations include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cows (BSE or mad cow disease), Kuru in New Guinean tribes (believed to be transmitted through cannibalism) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

Creutzfeldt Jacob Disease can be acquired from ingestion of infected foods (variant CJD) or it can be

caused by genetic mutations, either familial (inherited) or spontaneous (most common form).

The disease presents initially quite insidiously with impaired memory, changes in personality, loss of muscle coordination and visual disturbances. Progression is especially rapid in variant CJD cases that typically present a higher prion load. There is currently no cure for the disease and management is mainly supportive.

Edited by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

Reviewed by: Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 163