Next Lesson - Development of the Reproductive System

Abstract

- The pelvic floor has many functions. It supports the pelvic organs (especially with increased intra-abdominal pressure), is important in continence, and helps to facilitate childbirth.

- The pelvic floor is made up of:

- The levator ani muscles (deep muscles) - pubococcygeus, puborectalis and iliococcygeus

- The superficial muscles - bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus and superficial transverse perineal

- The ligaments - cardinal ligaments, pubocervical ligaments and uterosacral ligaments

- The perineal body

- The urogenital diaphragm

- The neurovascular supply to the pelvic floor includes the pudendal nerve and vessels to the perineum, as well as direct branches from S3 to S4 to the levator ani muscles.

- The organs of the pelvis can collapse into the space occupied by the vagina. An anterior prolapse involves the bladder (cystocele) or urethra (urethrocele). A central prolapse involves the uterus or the ‘vault’ of the vagina following hysterectomy. A posterior prolapse involves the rectum (rectocele) or loops of bowel (enterocele).

- Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse include age, parity, oestrogen deficiency and increased abdominal pressure. Management can be non-surgical (pessaries) or surgical (mesh supports).

- Urinary incontinence relating to the pelvic floor is stress incontinence. Risk factors include increased age and oestrogen deficiency. Management includes pelvic floor muscle training, and slings.

- The pelvic floor is often damaged in childbirth. This can be through accidental trauma such as tears, or surgical trauma such as an episiotomy. This can be performed in an attempt to widen the birth canal to prevent damage to the anal sphincter or rectum.

Core

Support is facilitated by 3 main methods.

Suspension - this maintains the pelvic organs in the pelvic cavity by providing a strong, sling-like support inferiorly in the pelvis.

Attachment - the vagina is supported by its attachments to the endopelvic fascia, levator ani muscles and the perineal body.

Fusion - support from the fusion of the urogenital diaphragm and the perineal body.

A key function of the pelvic floor is to facilitate urination and defecation and to maintain continence when not attempting to use the toilet.

The pelvic floor maintains the position of the pelvic organs during episodes of high intra-abdominal pressure, such as sneezing, coughing, or laughing.

The pelvic floor also contains the birth canal and helps to facilitate childbirth.

Composition of the Pelvic Floor

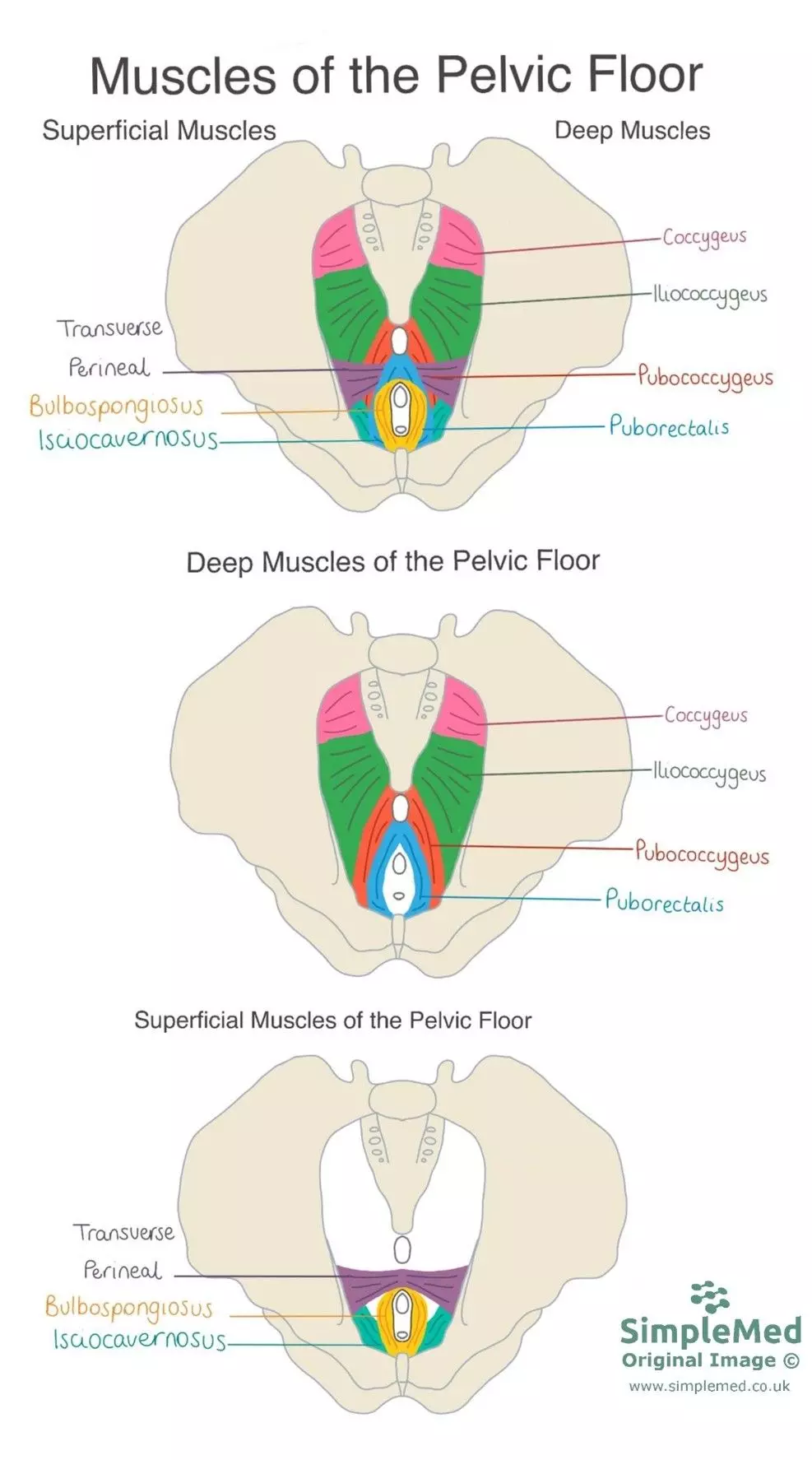

The levator ani are a U-shaped set of muscles that encircle the urethra, vagina and rectum. Anchored to the pubis and ischial spine, with fibres arising from the obturator fascia, they spread in a fan shape and act like a sling to support the pelvic organs. The levator ani has three components: pubococcygeus, puborectalis and iliococcygeus. The names of the muscles denote their attachments i.e. pubococcygeus originates from the pubis and inserts at the coccyx. Some fibres, particularly from pubococcygeus, contribute to the perineal body in the midline, while others form slings around the pelvic viscera.

The levator ani muscles sit very close to the coccygeus muscle, which is one of the deep muscles of the pelvic floor but is not part of the levator ani group.

There are also three superficial muscles: bulbospongiosus (encircles the labia in females or sits around the base of the penis in males), ischiocavernosus (along the line of the ischium), and the superficial transverse perineal. They aid in continence. If there is traumatic injury to the perineum these muscles are most commonly damaged. In some episiotomies, fibres of the superficial transverse perineal may be cut to aid childbirth, although episiotomy does not reliably prevent perineal tears and is performed only when clinically indicated.

Diagram - Muscles of the pelvic floor. It is divided into superficial and deep layers (shown together on the top image and then separately in the next two images)

SimpleMed original by Dr. Maddie Swannack

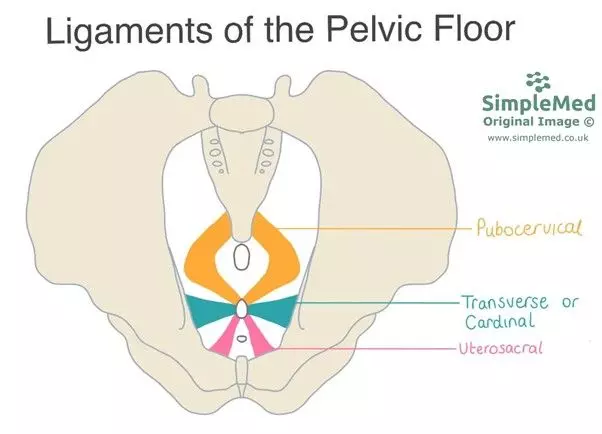

All the ligaments in the pelvis aid in the support of the uterus.

The cardinal ligaments (also known as the transverse ligaments) are situated along the inferior border of the broad ligament of uterus. They arise from the side of the cervix and the lateral fornix of the vagina, and attach to the lateral pelvic wall at the level of the ischial spine.

The pubocervical ligaments attach from the cervix to the posterior surface of the pubic symphysis.

The uterosacral ligaments attach the cervix to the sacrum. They are also known as the rectouterine ligaments and support the uterus.

Diagram - Ligaments of the pelvic floor

SimpleMed original by Dr. Maddie Swannack

The central point in the perineum where a number of ligaments and muscles coalesce. It lies between the vagina and the anus. It is key in maintaining support for the organs of the pelvis.

This term is traditionally used to describe the structures of the deep perineal pouch in the anterior part of the pelvic floor, including muscles and associated fascia related to the urethra, vagina and perineal body.

The pudendal nerve, pudendal arteries and pudendal veins supply the pelvic floor and perineum. The word pudendal comes from the slightly prudish Latin ‘to be ashamed’ reflecting its role in supplying the perineum and genitalia.

The uterus, bladder or rectum can all collapse into the vaginal space if inadequately supported. This can have various sexual, urinary or gastrointestinal side effects including pain and infection, and can be very psychologically troubling for the patient. Prolapses will often present with a feeling of dragging, bulging or a sensation of tissue descending into the vagina.

Prolapses can be classified by their origin.

An anterior prolapse involves organs anterior to the vagina including:

- Cystocele - bladder prolapses into the vaginal space

- Urethrocele - urethral collapse

- Cystourethrocele - both bladder and urethra

A central prolapse is a uterine prolapse in which the uterus collapses down into the vaginal space. Central prolapses can occur even after a hysterectomy has removed the uterus. Known as a ‘vault’ prolapse the superior portion of the vagina collapses downwards.

A posterior prolapse can involve:

- Rectocele - rectum prolapses into vaginal space

- Enterocele - loops of colon pressing across the rectouterine space

Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse: increased age, parity (having given birth, the more children the higher the risk), number of vaginal deliveries, oestrogen deficiency (usually seen during the menopause), and chronically increased abdominal pressure (for example caused by obesity).

Management strategies depend on how the patient is coping, severity of prolapse and their general health:

- Non-surgical - pessaries to provide additional support +/- topical oestrogen, pelvic floor exercises.

- Surgical - hysterectomy (if a central prolapse), or other operative repairs in carefully selected cases.

Goals for recovery should include the patient’s expectations and likely recovery.

There is risk of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) if the pelvic organs are inadequately supported. SUI occurs when urine leaks from the bladder during episodes of increased abdominal pressure. Usually increased pressure will not cause leakage, however, if the pelvic floor muscles are not adequately supporting the urethra, the pressure cannot be resisted and leakage occurs.

Risk factors include increased age and oestrogen deficiency (usually due to menopause).

Management strategies include pelvic floor muscle training through pelvic floor exercises. If conservative interventions are not effective surgical interventions can be considered including surgically creating slings to support the urethral sphincter.

Vaginal childbirth can be traumatic to the pelvic floor because the fetal head stretches the structures of the pelvic floor. In extreme cases this can cause tearing of the perineum and underlying structures.

Vaginal tears are graded as follows:

- Tear involves the perineal skin only

- Tear extends into the perineal muscles

- Tear extends into the anal sphincter complex

- Tear extends through the anal sphincter complex and anal epithelium

Tears of a higher grade and severity can have lifelong consequences through the damage they cause to the structures of the perineum especially to the perineal body. This factor links to why increased parity is a risk factor for pelvic floor dysfunction.

An episiotomy is a surgical incision made to the perineum in selected situations such as fetal distress or instrumental delivery, and is recommended by NICE to be used restrictively rather than routinely.

It involves the cutting of bulbospongiosus and the transverse perineal muscles at an oblique angle to relieve pressure on the perineum allowing for more space to deliver the child and to reduce the risk of a high grade tear. The procedure is a point of contention for some practitioners over the indications for performing an episiotomy. In brief, the debate is whether to perform the procedure in these specific circumstances or to pre-emptively perform the incision to prevent damage.

The pelvic floor can be weakened through childbirth, age and chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure. This can have many consequences, such as urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse, which can cause pain.

To help strengthen the pelvic floor, a number of exercises can be performed. A common regimen is the Kegel exercises. The first step is to identify the pelvic floor muscles. This can be done by briefly stopping urination mid-stream to identify the muscles, but this should not be practised regularly. The muscles that are clenched to stop the stream of urine are the muscles of the pelvic floor. Another (less technical and more unconventional) method of figuring out the pelvic floor muscles is to imagine sitting in a bath of eels and clenching the muscles to stop the eels getting into the vagina. This upward clenching motion uses the pelvic floor.

Once the muscles of the pelvic floor are identified, Kegel exercises can be performed. The muscles should be contracted for 5 seconds, then relaxed for 5 seconds. This should be repeated 10 times, ideally three times per day. The exercises should be continued even when improvement is noticed. This will help to strengthen the pelvic floor to lessen the effects of or prevent the symptoms of pelvic floor weakness.

Edited by: Dr. Ben Appleby and Dr. Thomas Burnell

Reviewed by: Dr. Marcus Judge

- 11634