Next Lesson - Malignant Breast Disease

Abstract

- The breast is prone to many different conditions and disorders due to its intricate structure and function.

- This article discusses the common benign conditions from infections and developmental disorders to different benign tumours, as well as how these different conditions are both investigated and managed in clinical settings.

- Benign breast disorders are investigated by mammography or ultrasound scan.

Core

There are lots of different conditions involving the breast and it is crucial to identify which of these are benign, and which are malignant.

Benign conditions do not themselves invade or metastasise, and so are often simpler to manage. However, some benign conditions are associated with an increased future risk of malignancy, which can blur the distinction in clinical practice. Benign conditions include infections, developmental disorders and tumours, with each condition managed differently, from medical treatment to surgical treatment, to being left alone.

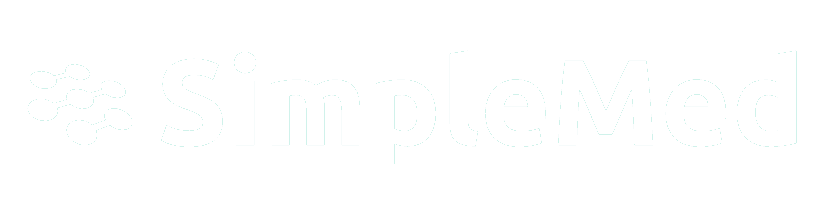

Developmental disorders are often associated with accessory breast tissue seen in an area that is not normally associated with the breast. This can be ectopic stromal tissue or more commonly extra nipples, known as polythelia. They usually present along the embryological mammary streak or “milk lines” as depicted below.

Diagram - The embryological mammary streak path

Creative commons source by The Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Gynaecomastia is the enlargement of the male breast due to a relative decrease in testosterone and increase in oestrogen. It can be either unilateral or bilateral. Gynaecomastia itself is benign and does not usually increase the risk of breast cancer, although breast cancer can still occur in men and suspicious features require assessment.

It is mainly seen in neonates (due to increased maternal oestrogen in circulation), puberty (transient gynaecomastia as oestrogen production peaks before testosterone), in the elderly or in those with excessive alcohol consumption (a reduction in liver function due to age or cirrhosis means that oestrogen cannot be metabolised). It is also a known side effect of some drugs such as spironolactone and anabolic steroids.

The most common benign breast disorder is fibrocystic change, occurring most commonly in women aged 20 to 50.

It presents with pain and masses in the upper outer quadrant of the breasts, most prominent in the week before menstruation. Symptoms ease at the start of the period. This discomfort is caused by a combination of localised fibrosis, inflammation and cyst formation.

If the symptoms are bilaterally symmetrical and synchronised to the woman’s menstrual cycle, a diary recording the symptoms may be helpful, and examination should ideally be performed mid-cycle. Once confirmed as fibrocystic change rather than a mass the patient should be reassured and then receive symptomatic management, which includes analgesia and a well-fitting bra. If invasive management is required for a symptomatic cyst, it often resolves after fine needle aspiration.

Duct ectasia involves the dilation of one or more of the lactiferous ducts in the breast, leading to blockage of the duct and inflammation. Key features include nipple discharge (bloody, serous, creamy white or yellow are all possible), retraction of the nipple, chronic periductal inflammation and abscess formation.

Management is usually conservative, with reassurance and symptomatic treatment. Surgical excision of the affected duct may be considered for persistent or troublesome symptoms, and referral is often made to exclude malignancy when features overlap with breast cancer. This referral is commonly done under the breast cancer pathway, as nipple discharge and masses could be suggestive of breast cancer.

Acute mastitis is an inflammatory condition of the breast that predominantly occurs during breastfeeding. The lactiferous sinuses become infected by bacteria (commonly Staphylococcus aureus) entering via the nipple. The breast becomes painful, swollen and erythematous, and patients will often present systemically unwell with signs like fever, rigors and fatigue.

Infection is most likely if stasis of the milk occurs, through blocked ducts or unilateral breast feeding.

Initial management of mastitis is to try to return the flow of milk in the ducts by massaging the breast to “wash away” the infection. This can often be done by the woman at home, through expressing all the milk held in the infected breast. This can be done through feeding the child (there is little risk of passing the infection on), using warm compresses and using a breast pump. If this does not relieve the infection, antibiotics such as flucloxacillin may be considered.

Mastitis can occur without breastfeeding, relating to skin irritation of the breast, such as through eczema. In these women, antibiotics are usually indicated promptly, with the choice guided by likely organisms and local policy.

If the infection is left untreated, it can lead to a breast abscess and sepsis, and so it is important to check the observations of every patient presenting with mastitis. This is particularly important in older patients as stasis of milk is far less likely to be the cause, and there is an increased risk of an underlying pathology.

If the red, painful and swollen breast does not improve with antibiotics then a referral should be made to rule out inflammatory breast cancer, which can present similarly due to diffuse lymphatic infiltration.

Cysts in the breast are difficult to distinguish from solid tumours on examination, meaning that referral for imaging should be made. They are fluid filled sacs often surrounded by fibrous tissue, presenting between the ages 35 and 50 as mobile and smooth masses. Symptomatic cysts can be aspirated for relief; surgical removal is rarely required.

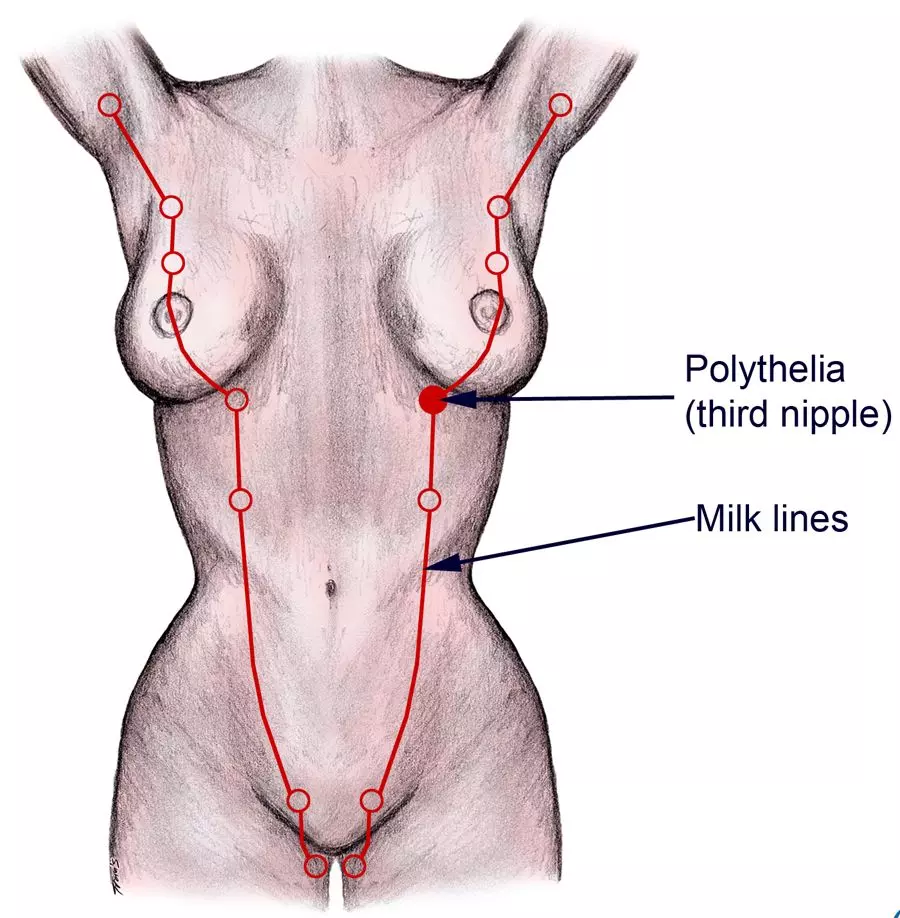

Fat necrosis presents as irregular, firm, palpable masses with or without skin changes meaning it mimics breast cancer clinically, and so should be referred for further imaging. The necrosis is the result of an inflammatory response either post trauma or surgery of the breast, and so this should always be asked about in the history.

Image - Histological breast tissue showing fat necrosis. There are necrotic adipocytes surrounded by an inflammatory response with cholesterol clefts

Creative commons source by Department of Pathology, Calicut Medical College [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

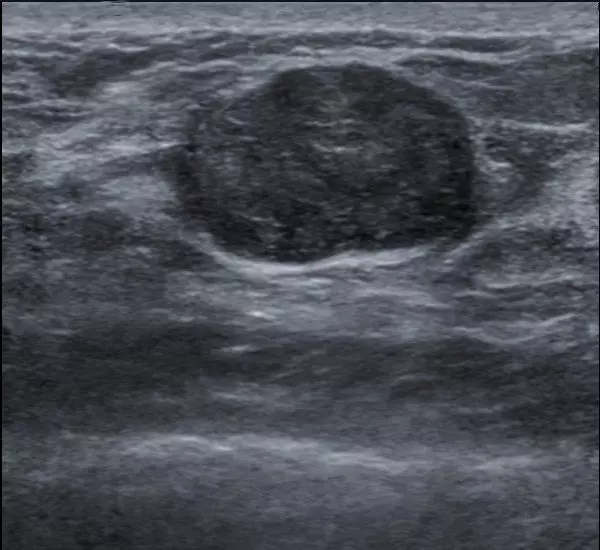

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign tumour of the breast and occur at any age, but more prominently under the age of 30.

They are intralobular stromal tumours, formed by a proliferation of both stromal and epithelial elements - this is key for it to be a fibroadenoma. They are classified as benign tumours, representing a benign neoplastic proliferation of stromal and epithelial tissue.

There are frequently multiple and bilateral lesions in these women, and present as smooth, round, non-tender and highly mobile masses with regular borders on ultrasound scans or mammograms.

They can have either a solid or cystic consistency and appear to have a hormonal aetiology as hormone replacement therapy increases the incidence rate. It is possible for the tumours to grow very large and replace most of the breast. When they are removed they appear rubbery and grey white. Fibroadenomas have no potential to become metastatic.

Image - Ultrasound image of a fibroadenoma

Creative commons source by Nevit Dilmen (talk) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Phyllodes tumours are breast stromal tumours which present in older women and have a higher probability of becoming malignant (about 5%). They can be very large and involve the entire breast.

They are nodules of proliferating stroma covered by "leaf-like" epithelium. The stroma in phyllodes tumours contains more atypical and mitotic cells than it would in a fibroadenoma.

Treatment is excision with a wide margin to try and prevent local recurrence of the tumour. The malignant types are very aggressive and can metastasise along the blood vessels, meaning fast investigation and diagnosis is important.

Other generalised benign stromal tumours like lipomas, leiomyomas and hamartomas can also occur in the breast.

Investigating Benign Breast Disorders

It is important to treat any breast abnormality with a high index of suspicion, because it is very difficult to confirm whether an abnormality is benign without any imaging. This means that unless a mass can be determined as 100% benign, it should be referred on the suspected breast cancer pathway for mammography or ultrasound scan.

The most common benign breast disorders that are classified as a ‘watch and wait’ pathology are:

- Mastitis - infection of the breast can be treated in primary care and is fairly specific. Referral only needed if does not resolve.

- Fibrocystic change - this disease may not need referral if it is without doubt cyclical.

Any other pathology of the breast discussed in this article cannot be definitely distinguished from a malignant lesion on palpation alone, and should be referred for imaging.

Edited by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

Reviewed by: Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 3911