All done here! Check out our other subjects!

Abstract

- Monoclonal antibodies are used for both therapeutic as well as diagnostic purposes.

- Types of antibodies are classed based on their composition and organism of origin.

- Monoclonal antibodies are a promising therapeutic tool but also carry side effects that can range from mild to severe immunological reactions.

Core

Antibodies (also known as immunoglobulins, Ig) are Y-shaped proteins produced by B-cells (plasma cells) that are activated by the adaptive immune system when exposed to antigens (see article on adaptive immunity).

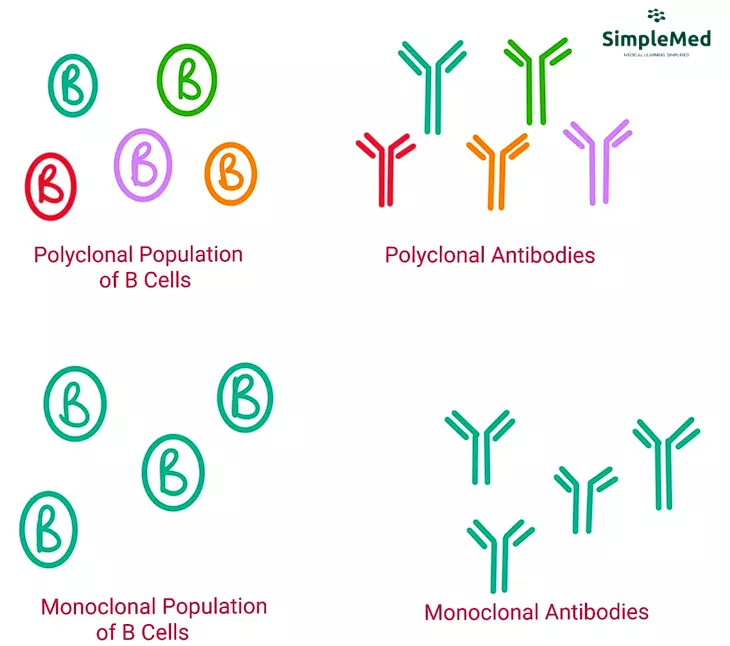

The antibody population produced in the body is polyclonal. This means that there are multiple B cells producing multiple different types of antibodies all simultaneously, creating a population of antibodies that are all different and all bind to different antigens.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are antibodies made artificially by creating a population of identical cloned B-cells derived from a single parent B-cell. Every antibody in this monoclonal population will be identical.

Diagram - Difference between a population of polyclonal antibodies produced by a variety of parent B cells, and a population of monoclonal antibodies produced by a single type of parent B cell

SimpleMed original by Dr. Maddie Swannack

Types of Monoclonal Antibodies

There are 4 types of monoclonal antibodies based on the origin of their components and they can be differentiated through their nomenclature:

Murine Antibodies (end in -omab) - they are entirely derived from a mouse source. These have an increased potential for immunogenicity with a high risk of triggering an allergic reaction when used in humans. They also may not be acceptable to some patients if, for example, they hold religious beliefs on vegetarianism.

Chimeric Antibodies (end in -ximab) - these are of mixed origin (65% human) with the ‘stem’ of the Y shape antibody being human in origin, and the ‘arms’ of the Y shape antibody being of mouse origin. These have a lower risk of allergic reaction than purely murine antibodies but are still prone to causing allergy when infused in humans.

Humanised Antibodies (end in -zumab) - these are of mixed origin but with a minimal murine component (>90% human), the murine (mouse) part only representing the portion binding to the target antigen.

Human Antibodies (end in -umab) - these are entirely derived from a human source.

Humanised and human antibodies present a much lower risk of immunogenicity for use in humans because they are recognised by the immune system as ‘self’.

Clinical Use of Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are used in research for both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. Understanding which antigens are associated with specific cancer cells and which are found on normal tissue cells helps choose antigen targets for developing appropriate monoclonal antibodies.

When used for therapeutics, they can work in multiple ways:

- Bind to cell surface receptors (antigens) to activate or inhibit signalling pathways within the cell.

- Induce cell death by binding to antigens and activating antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC).

- Bind to antigens prompting internalisation (switching to the inside of the cell surface membrane), allowing them to release toxins directly into the target cancerous cells.

- Block inhibitory immune checkpoints on T-cells, thereby enhancing T cell mediated immune responses against cancer cells.

Conjugated monoclonal antibodies are monoclonal antibodies that have been tagged with either a cytotoxic (chemotherapy) drug or a radioactive particle, allowing delivery of treatment to cells expressing the target antigen. This helps produce a more localised effect and can reduce systemic side effects, although some binding to normal tissues may still occur if the antigen is also expressed on healthy cells.

Monoclonal antibodies are also used in routine laboratory techniques such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), immunohistochemistry and Western blotting.

Side Effects of Monoclonal Antibodies

As mentioned previously, murine and chimeric monoclonal antibodies have a higher potential for triggering an immunogenic response when infused in humans than humanised or human antibodies, but the response can vary between patients.

Some patients will experience no symptoms or mild symptoms such as fatigue during treatment with monoclonal antibodies.

Others will have a mild reaction following the initial infusion and tolerate subsequent infusions better.

Finally, a few people develop severe infusion-related immunogenic reactions where the body’s immune system reacts to the presence of foreign antibodies.

In order to manage infusion-related reactions appropriately, patients need to be well informed about the red flags indicating a potential reaction to the infusion and be made aware that they should contact clinical staff immediately if they experience unexpected side effects. Precautionary measures can also be taken by prescribing prophylactic steroids, antihistamines, or paracetamol to lower the risk of an immunogenic response by inhibiting inflammatory processes. Monoclonal antibody infusions should always be initiated at a slow rate and later increased in a stepwise manner if well tolerated.

Finally, appropriate emergency drugs to treat infusion-related reactions should always be readily available, or prescribed according to local protocol, prior to initiating patient treatment.

Edited by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

Reviewed by: Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 216