Next Lesson - Falls

Abstract

- Ageing is a relative concept. An active 90-year-old can have the same baseline as an ill 60-year-old, and so medical professionals use this baseline to decide how best to manage their patients. This being said, with age comes an accumulation of co-morbidities, risk factors, polypharmacy, and an increased risk of frailty.

- Elderly patients are challenging and will not necessarily present as expected, often attending appointments complaining about becoming more tired, confused, or having 'off legs'. It is the job of the medical professional to look at the clinical problems beneath this surface and decide how to take care of the patient appropriately so that they can live day to day as well as possible.

- Older patients have lots of social factors to contend with too, from becoming isolated when loved ones pass away, feeling like a burden to their children, and often the potential of poverty weighing on their mind. The focus with these patients should be on both the urgent and the important to provide the best level of care.

Core

Ageing and How it Affects the Body

Ageing can be described as the progressive functional decline of the body's organ systems, and each person responds differently. Much of this decline comes from a loss of tissue elasticity over time leading to reduced compliance of that tissue. Compliance is the tissue's ability to stretch and expand when it becomes filled, then return to its normal form when it empties. Examples include the airways or the different chambers of the heart. When organs lose compliance they become more solid and brittle.

The skin becomes much thinner and wrinkles with increasing age. There is loss of vasculature and elasticity of the skin, both of which are associated with the reduced quantity of collagen fibres present in the skin. This means that elderly patients are much more susceptible to bruising after any minor impact, because the small subcutaneous blood vessels become more friable and fragile, meaning they break and bleed more easily. Elderly patients also often have poorer venous access (meaning they are harder to cannulate) than their younger counterparts. This is because their veins move around much more as they are not as tethered to the underlying tissues, as well as being more easily damaged.

With advancing age, changes occur in respiratory mechanics. Lung compliance tends to increase due to loss of elastic recoil, while chest wall compliance decreases. Measures such as FEV1, FVC and vital capacity are reduced, whereas TLC (total lung capacity) is usually preserved or may increase slightly. These changes reflect reduced elastic recoil of the lungs and altered airway support.

The alveoli and terminal branches of the airways are more susceptible to collapsing as they have less elastic support keeping them patent.

Respiratory complications post-operatively such as atelectasis, pulmonary emboli and pneumonia are increasingly common in the elderly.

The decline in the cardiovascular system occurs when larger blood vessels lose elasticity and become less compliant. This results in an increased vascular resistance and hypertension which leads to left ventricular strain and hypertrophy.

Over time, the electrical conducting cells in the heart decline in number, resulting in conditions such as heart block, ectopic beats, atrial fibrillation, and arrhythmias becoming more commonplace.

Cardiac output decreases with each passing decade as stroke volume & contractility of the heart decrease. Any dysfunction of the atria causes their contraction to be impaired. As a result, ventricular filling is reduced. Atrial contraction normally contributes around 20 to 30% of ventricular filling, so impairment of atrial function can lead to a reduction in cardiac output.[1].

These changes can contribute to reduced exercise tolerance and haemodynamic reserve, although systolic blood pressure commonly increases with age.

Disorders of the central nervous system are often secondary to issues with the vasculature supplying the nerves. Atherosclerosis and hypertension are among the most common causes of this impaired supply.

With age comes cerebral atrophy with reduced neuronal density that strongly correlates with degrees of cognitive decline[2].

The renal system declines in function throughout the entire lifespan. This can be seen as the glomerular filtration rate (what is used to measure kidney function) decreases by approximately 1% each year after the age of 30[3]. This is due to the loss of glomeruli throughout the renal cortex. As a result of vascular deficiencies, the decreased renal perfusion leads to reduced renal function, and increased glomerulosclerosis.

Diabetes has an increased prevalence in the elderly and the microvascular complications of the disease are known to worsen renal function. Elderly people are often prescribed more nephrotoxic medication such as NSAIDs. Drugs that affect renal haemodynamics, such as ACE inhibitors, can also contribute to a fall in glomerular filtration in certain situations, for example during dehydration or acute illness, and therefore require monitoring. Elderly male patients who have enlarged prostates are also at risk of obstructive nephropathy.

Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of many drugs are altered in elderly patients as the rates at which they are absorbed, metabolised, and cleared can all change dramatically with the changes in the functioning of various organs. Patients often have an increased sensitivity to drugs that depress the central nervous system. Too high a dose can leave them with cognitive and physical impairments. The cumulative anticholinergic effects of certain medications are described as a high anticholinergic burden. These medications need to be monitored and adjusted accordingly to prevent this from happening.

Elderly patients with reduced hepatic and renal function have both slower metabolism and elimination of medications respectively. Often this means that the medications take longer to take effect and longer to get rid of. Again, doses should be adjusted accordingly. Intravenous anaesthetics can often take much longer to take effect in elderly patients as the decreased cardiac output increases the amount of time it takes for the drug to reach the brain.

Elderly patients often have either a reduced total body water or increased amounts of adipose tissue leading to an altered volume of distribution for some drugs.

Those patients with decreased plasma proteins in their blood will have reduced protein binding of any medication that they take. This means that there are increased levels of free drugs available in the blood and so the circulating dosage of any of these medications is effectively increased.

Elderly patients are commonly taking multiple medications every day to treat multiple different conditions and so are at risk of polypharmacy, defined as taking 5 or more medications a day. This phenomenon is known to increase the risk of falls and decrease patients' quality of life.

A small amount of cognitive decline is to be expected with age through natural brain atrophy. However, conditions such as dementia can worsen this decline significantly, leading to significant changes in cognition and behaviour, and leaving them in an incredibly vulnerable state both medically and socially.

Dementia is becoming an increasingly common condition with the UK’s ageing population. Over ¼ of patients in acute hospital beds suffer with dementia and a comparably high proportion of care homes and community hospital residents[4]. These patients often require carers in the form of either their relatives or a professional package of care. The life-changing diagnosis is made on information gathered from the history, any examinations performed and a full cognitive and mental state exam. Ideally, this should be performed in the patient’s usual environment such as at home, when the patient is properly awake, relaxed, and ensuring that they are not in any pain. An examination done under these conditions will produce the most accurate results from which to base the diagnosis on.

There are multiple different subtypes of dementia that are discussed in the dementia article. They each present slightly differently and have different features. It is important to identify which type a patient has to predict their prognosis and offer any medical interventions that may help.

The early signs of dementia which are often picked up are memory issues or an inability to perform more complicated cognitive tasks. It is important to remember that not every patient with dementia has lost their capacity to make decisions for themselves, but the prognosis is that of a progressive decline to the point where the patient is unlikely to still have any remaining capacity.

Patients presenting with confusion should also undergo a variety of investigations to screen for physical causes, such as blood tests looking for any undiagnosed hypothyroid disease. If there are concerns about a patient’s mental state, they should be referred to memory clinics where radiological imaging such as a CT or MRI scan of the head will be performed and reviewed. Every patient with a new diagnosis of dementia should be assessed on their ability to care for themselves, and caring measures should be put in place if they are required.

Sadly, there is currently no cure for dementia, so the aim of treatment is to temporarily stop or slow progression of the cognitive decline. Medication can play a role in reducing any exacerbating factors that may worsen the decline and help to relax agitated patients, but socialising and maintaining a routine are vital in preventing decline.

While patients still have the capacity, discussions around advanced care planning should be had to decide how they would like to be cared for at the points when they are deemed that they can no longer look after themselves. As these patients near the end of their lives, the palliative care services should be liaised with so that they are kept at peace and comfortable when their time comes.

Common Issues in Elderly Patients

Pressure sores are a source of great discomfort and pain for any bedbound patient and they can often be prevented with appropriate care. The constant pressure and irritation to the same area of the body from the bed progressively wears away the skin and underlying tissues that overlie a bony prominence supporting the patient’s weight. As well as being incredibly painful for the patients, pressure sores pose a large infection risk if the skin barrier is broken and are heavily associated with an increased mortality rate. This is all preventable by simply moving and adjusting the patient's position in the bed at regular intervals.

Malnutrition is worryingly common in the elderly population and again is preventable. It is a discrepancy between the calories and nutrients that the individual eats and what they require to maintain their health. This can either be in the form of too much or too little intake, however, in this context the more harmful is considered to be an inadequate intake (i.e. too little). It is very important therefore to assess every patient with a screening tool for malnutrition. A commonly used tool is the malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST). The full tool can be found here. It uses the patient's BMI, any unplanned weight loss in the past 3-6 months, and the patient’s disease acute disease effect (if the patient is acutely ill and there has been or is likely to be no nutritional intake for >5 days) to predict their risk of malnutrition. This then guides your management plan and advises if a dietician review is required.

There are many reasons why a patient may become malnourished:

- They may not be eating as don’t like the food in hospital or at a new care home.

- The patient’s dietary requirements may not be being met through what they are eating.

- Patients may be unable to cook for themselves at home.

- They may be too weak to eat and require assistance cutting up food or even need to be fed.

- They may have a poor swallow or cannot chew food for a variety of reasons, for example missing teeth or ill-fitting dentures.

- Patients who are systemically unwell lose their appetite and refuse food, and do not absorb nutrients well even when they do eat.

Dietitians can help to rebuild a patient’s nutritional status and educate them or put in place measures to prevent them getting to this state again. Dietitian consultations should also occur with any patients who are at risk of malnutrition and are receiving surgical care, as this could require a period of starvation.

Frailty is a risk state which arises from the accumulation of deficits throughout the patient’s life. Or more simply put, people are frail when they have lots of things wrong with them.

Frailty is by no means just an age-related phenomenon as not everyone of the same age has the same co-morbidities or risk of death, and patients may have different levels of frailty at different ages.

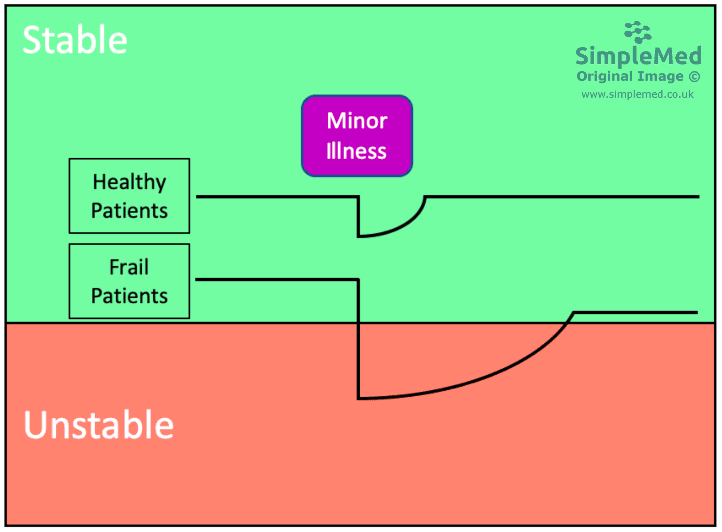

Frailty as a concept can be explained through the effect of a minor illness, or the addition of a new medication on a patient. If a patient is fit and healthy, a minor illness or new medication causes a small dip in their overall baseline wellness and before resolving with a short, swift and full recovery.

When frail patients sustain the same insult, they will have a much greater drop in function, a far longer recovery period which will not return them to their previous baseline. This drop-in function can push patients into an unstable state, that often manifests itself in the form of falls and delirium. As a general rule, the response to an insult is disproportionate to the size of the insult.

Diagram - The difference that a minor illness can make on two patients, one healthy and one frail. Notice how the frail patient drops much further, takes longer to recover, and ends up on a much lower baseline

SimpleMed Original by Dr. Tom Bradley

Frailty is typically a linear picture throughout life, with patients becoming frailer as they get older as co-morbidities accumulate. Life-changing events such as car crashes or certain diseases can alter this course and leave patients frail at much younger ages.

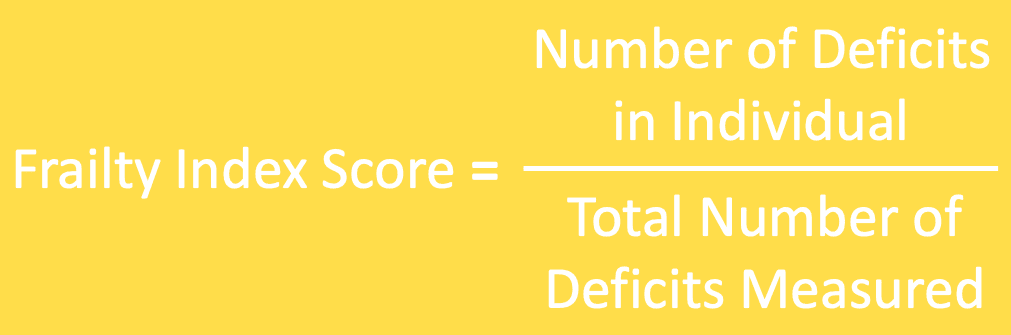

Frailty is measured using the Frailty Index Score, a tool that is used to calculate the frailty of every patient over 65 that comes into A&E. Patients are categorised into being fit, being of mild frailty, being of moderate frailty, and being of severe frailty and these categories are used to guide management.

Diagram - The formula used for the frailty index score

SimpleMed original by Dr. Tom Bradley

The index score quantifies the number of things that are contributing to the frailty of this patient. For example, if out of a possible 70 things that could go wrong with a patient, they only had 5, a patient would have a very low frailty index score (5/70) and be deemed to be healthy. There is a strong correlation between the worse a patient’s frailty index score, and adverse outcomes for treatment.

Frail patients require individual assessments that look at their baseline functioning and their ability to perform activities of daily living. As part of this assessment, they will often be reviewed by a multi-disciplinary team made up of doctors, dieticians, nurses, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists to name but a few who will assess every aspect of the patient’s life and decide how best to care for them. These assessments may mean that the patient is deemed not suitable for certain interventions, as they are ‘too frail’ to be able to recover well afterwards.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482421/

[2] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10331700/

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4741051/

[4] https://www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/hospitals/

Edited by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

Reviewed by: Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 185